7 Things an American learned in New Zealand

I spent three weeks traveling through New Zealand, starting in Auckland at the top of the North Island, then traveling by bus, ferry and plane towards Queenstown in the South Island. Along the way I met locals, ate at fast food chains and nice restaurants, hiked in several national parks and gradually accumulated knowledge of differences between New Zealand and the United States. It has much in common with the United States: both are former British colonies, English speaking, with fully developed economies. With so much in common, the differences are all the more surprising when they appear.

1. European New Zealanders are still referred to using a native Maori word

The first thing I noticed was the inflight magazine on my Air New Zealand flight from Los Angeles to Auckland:

The title of the magazine, ‘Kia Ora’, is the native Maori people’s word for ‘Hello’. Inside I found reference to another term – ‘Pakeha’. I noticed this word again in newspaper articles, generally in a sentence referring to ‘Maori and Pakeha’. When Europeans first arrived in New Zealand several hundred years ago, the native Maori people used the word ‘Pakeha’ to refer to them, a word meaning ‘foreigner’ or ‘white person’. Incredibly, this word has widespread usage by European New Zealanders today when referring to themselves. John Chambers in ‘A Traveller’s History of New Zealand’ explains how unprecedented this is:

“This usage, whereby the majority and more economically powerful and formerly imperial ethnic group unremarkably uses a term given them by the native people is perhaps unique in history. It is as if modern United States citizens of European descent, naturally and unselfconsciously in everyday language were to call themselves ‘Palefaces’ or some native-American term.”

The story of the Maori people mirrors similar stories of native peoples across the globe. Maori leaders signed a treaty with the British in 1840 turning over some land rights (the Treaty of Waitangi) and disputes over land began to occur. These conflicts, as well as disease, led to a decline in the Maori population until the 1900s. Today they make up about 15% of New Zealand’s population, and continue to struggle with higher rates of crime and health problems. If you’re a rugby fan, you’ve heard of the All Blacks, New Zealand’s national rugby team. Before some matches they perform a Maori Haka, a traditional war chant.

2. World War 1 was a huge deal for New Zealand

Just outside the center of Auckland, at the top of a hill surrounded by grassy fields, sits one of Auckland’s most iconic buildings, the Auckland War Memorial Museum. One of the first things I noticed inside was the heavy emphasis on World War 1 — even more so than World War 2.

The Great War has steadily faded in the American consciousness for the past hundred years. Hitler, D-Day, Pearl Harbor, Nazis, and the Holocaust are remembered vividly, but what do we remember from the First World War? Before I went to New Zealand, my memory from high school world history was a hazy mix of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, trench warfare, and black and white photos of soldiers wearing gas masks. If Vietnam and World War 2 are in the top tier of 20th century American conflicts ranked by their presence in our collective memories, World War 1 is on the second tier, above but not far from conflicts like the Korean War.

In New Zealand, World War 1 has top tier status. This is mostly a result of timeline and geography. New Zealand is a younger country than the United States, and had existed only briefly when the First World War began. It is also an isolated island country and avoided regional conflicts. Though they had been involved in other conflicts prior (e.g. sending troops to South Africa in the Second Boer War), World War 1 was their first large scale international conflict.

Since the signing of the treaty of Waitangi in 1840 by the native Maori leaders, New Zealand had been a British colony. When WWI started, many New Zealanders still had close ties with Britain and considered themselves proud to be part of the British Empire. When Britain declared war in 1914, many New Zealanders were prepared to help the Crown. Just over 100,000 New Zealanders served overseas during the war–10% of the population.

The casualty rate for these soldiers was 58% – 17,000 killed and 41,000 wounded. Almost two percent of New Zealand’s population was killed in the war. While this is on par with the United Kingdom, and less than France or Germany (deaths were closer to 4% of their population), it is huge compared with the United States, which lost ten times as many soldiers but had a population 100 times as large. Though the United States played an important role in the war, they entered very late. New Zealand was present from the beginning, which meant they took part in the failed invasion at:

Gallipoli

Later in my trip I visited Wellington, which sits on the south end of the North Island. In a prominent position on the waterfront is a museum referred to as ‘Te Papa’, a Maori phrase meaning ‘Our Place’. There is currently a major new exhibit there devoted wholly to Gallipoli. I tried to visit my first day in Wellington, but with a wait of well over an hour, I came back at open time the next day (and still had to wait almost a half hour).

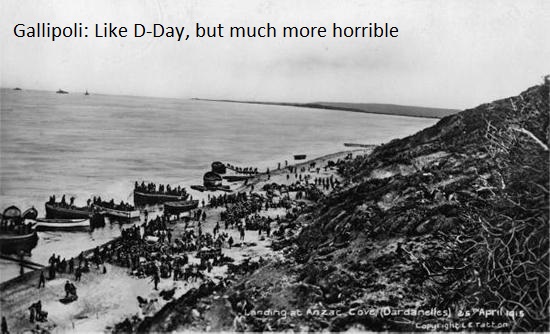

In 1915, New Zealand forces joined Australians, British, and others in a now infamous attempt to capture the Gallipoli peninsula, which controlled access to the strategically important Dardanelles Strait near Turkey. At first glance an American might find some things about this campaign ripe for comparison with our best remembered military battle: the D-Day invasion of World War 2. Both were large allied invasions, starting with a beach landing and moving inland to capture key territory. Winston Churchill had a hand in both — he originally proposed the Gallipoli Campaign.

(picture from here, landing at Anzac Cove on April 25th, 1915)

By every measure Gallipoli was more brutal than D-Day. New Zealand and Australian troops landed at Anzac Cove on April 25th, 1915. The beach had some protection, but was in range of Turkish artillery, and heavy machine gun fire prevented them from moving inland. Trenches were dug on both sides and the battlefield slowly took a similar appearance to the Western Front. The Allies launched several major offensives over the following months, all of which suffered devastating casualties, and all of which were pushed back. By the end of 1915 the Allies had almost entirely evacuated. Casualty rates on both sides were close to 60%.

No one disputes the bravery or sacrifice of the soldiers on D-Day, but however brutal it was, that invasion succeeded quickly. The Allies suffered approximately 10,000 casualties in the D-Day invasion. At Gallipoli the Allies suffered 250,000 casualties in a prolonged eight month conflict which ended in retreat. The stature of these battles in the respective national consciousness of each country is similar. New Zealand and Australia still celebrate ANZAC day on April 25th, the landing day at Gallipoli, as their major day of remembrance.

New Zealand also suffered major casualties later in the war on the Western Front and in other battles. In nearly every town I visited there was a World War 1 memorial of some kind. There were no American troops at Gallipoli, so for us it is largely a historical footnote, but its impact on New Zealand as a young country still forging a national identity cannot be understated.

3. ‘Free Wifi’ might mean ‘A little bit of free wifi’

I’m including this as a note of caution to future travelers. After leaving Auckland, I took a bus south to Rotorua. I had booked a single room in a cheap motel that advertised ‘Free Wifi’. At check in, the man behind the desk asked if I needed Wifi access. I said yes, expecting he would give me the password to connect. Instead, he handed me a small slip of paper that said ‘100 MB Wifi’, with a login code.

(these Zenbu vouchers were common)

100 MB of Wifi is fine to check email, but disappears quickly if you are scrolling through pages on TripAdvisor, and even more quickly if you are uploading pictures. I had the same data rationing experience in most places I stayed. At one Queenstown motel I was asked if I wanted ‘a little, a medium amount, or a lot of Wifi’. I chose medium, which was worth 300 MB of Wifi credit.

That said, everyone I met working at hotels and hostels was incredibly kind and accommodating. The one time I ran out of data, they found me an extra 100 MB of credit. But if you’re taking a lot of pictures, don’t expect to upload them all until you get to a country where unlimited Wifi is common (or else, expect to pay up).

4. New Zealand was once the world’s greatest bird paradise

When I failed to visit the overcrowded Gallipoli exhibit at the ‘Te Papa’ museum on my first day in Wellington, I turned next door to an exhibit on New Zealand’s natural history. My knowledge of New Zealand animal life was mostly the Kiwi, a symbol of New Zealand most people recognize, but it turns out that’s just one relic of the country’s history as a bird paradise.

The landmass of New Zealand was formed 80 million years ago when shifting tectonic plates caused it to separate from the supercontinent of Gondwanaland. Notably, this separation occurred before mammals had evolved. The Tasman Sea, which separates New Zealand and Australia, slowly widened. Until humans arrived, the only animals that could reach New Zealand were birds. The result? New Zealand became a bird utopia. The only mammals that existed in New Zealand were bats.

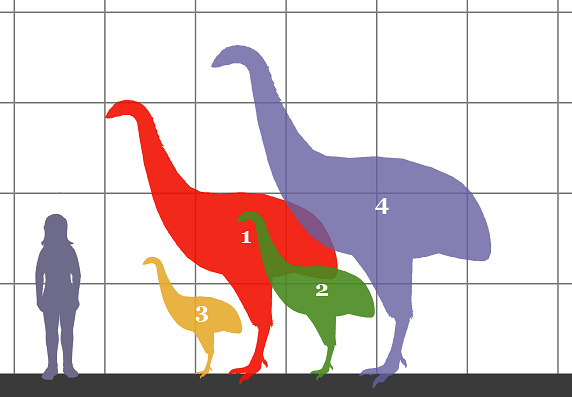

In isolation and without the presence of mammals, some of the largest birds to ever exist evolved in New Zealand (a phenomenon known as island gigantism). When flight no longer proved to be a competitive advantage, many birds became flightless. The Giant Moa that lived on the south island (#4 below) was the tallest bird species ever known to exist, a flightless herbivore that could reach plants up to 12 feet from the ground. The only predator of the Moa was the Haast’s Eagle, the largest eagle that has ever been discovered, which had up to a ten foot wingspan. The Kiwi, now the country’s national symbol, evolved as another flightless bird. It is a strange, nocturnal creature distinguished for laying eggs six times larger than a chicken’s–the largest in proportion to body size of any bird. They are still wild in certain parts of the country, but I saw one only in captivity.

(picture from here, scale of different Moa species)

What happened to all of these species? When the Maori people arrived in the 1300s, they hunted the Moa to extinction within 150 years. The Haast’s Eagle lost its primary source of food and quickly went extinct. The Kiwi survives, but along with many other native birds, it suffered from the introduction of species like ferrets and stoats. These fed on Kiwi eggs and necessitated conservation efforts which continue. The most common places for conservation are islands or fenced off peninsulas, utilizing the surrounding water as a natural barrier. Kiwis are common on Stewart Island in the Pacific below the South Island. While hiking around Lake Waikaremoana on the North Island, I passed by a fenced off peninsula on the lake dedicated to Kiwi preservation. Metal fences are driven several feet below the ground to prevent the ferrets and stoats from digging underneath.

Today, many outside plants and animals have been introduced. One tour guide I spoke to said, “If it walks on four legs, or loses its leaves in the winter, it was probably introduced by humans.” The most obvious is sheep, which have long outnumbered humans and cover the countryside.

(Sheep – introduced by humans to New Zealand)

5. New Zealand was almost the last landmass on Earth to be discovered

What about human settlement? After wandering through the exhibit on the natural history, I found some information on the first human settlers, the Maori people. For 80 million years New Zealand was home to mostly birds, a few reptiles and amphibians, and surrounded by vast oceans. It was not until 1300 AD that humans arrived, most likely on large canoes that had traveled from other Polynesian islands far to the northeast like the Society or Cook Islands. Americans might often be tempted to group New Zealand with neighboring Australia, but this is a point of stark contrast: in Australia, human remains have been dated to 50,000 years ago. New Zealand was the last major landmass to be discovered with one exception – Antarctica. (A New Zealander, Alexander von Tunzelmann, was a member of the first group known with certainty to have set foot on Antarctica in 1895).

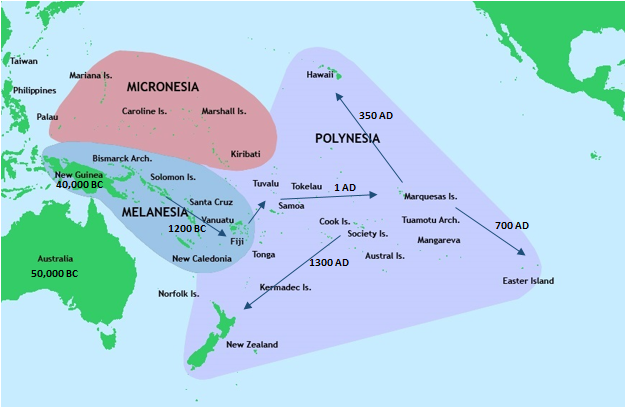

The map below shows approximate times a few islands in the Pacific were settled. Areas like New Guinea close to Southeast Asia were accessible and settled early. Polynesia was settled much more recently. Dates are estimates, and migration paths are derived by looking at the movement of cultural objects like pottery as well as by analyzing linguistic similarities between different island peoples. Interestingly, there is no evidence of the Maori ever returning home to islands in Polynesia. The trip to New Zealand was probably one way.

(original image from here)

6. New Zealand is a ‘Nuclear Free Zone’, which occasionally causes drama with the United States

While exploring Wellington, I came across something unexpected: a Japanese lantern housing a Peace Flame. This flame was gifted by Hiroshima, Japan in 1994 and originally lit from fires started by the atomic bomb.

(Peace Flame in Japanese lantern, located in Wellington)

Wellington declared itself ‘nuclear free’ with the passing of a resolution in 1982. Starting in the 1950s, the public was concerned about nuclear weapons testing occurring in the Pacific. Public opposition to nuclear weapons grew throughout the Cold War. Many towns passed resolutions declaring themselves ‘nuclear free’. The rest of the country followed suit in 1984, when the prime minister declared that nuclear ships or submarines would not be permitted to dock in New Zealand. Three years later, legislation was passed establishing New Zealand as a ‘Nuclear-free zone’.

Prior to this, New Zealand and the US had a long history of cooperation. In World War 2, more than 400,000 Americans were stationed in New Zealand before famous battles like Saipan and Iwo Jima. After the war, Australia, New Zealand, and the US signed the ANZUS treaty, a three way defense pact established in 1951. New Zealand sent troops to 20th century conflicts including the Korean War and Vietnam (which was very controversial, as it was in the US). But as the 20th century progressed, New Zealand grew more independent and less reliant on both the UK and the United States.

When the prime minister declared New Zealand ‘Nuclear Free’, the United States was not pleased. The US refused to confirm or deny if their ships or submarines were nuclear. Effectively, no US ships could land in New Zealand. As a consequence, the New Zealand-US link of the ANZUS treaty was terminated (both links with Australia still remain effective). This was a low point in relations, which have since since improved. New Zealand sent troops to the first Gulf War and Afghanistan, and they remain a part of the ‘Five Eyes’ intelligence sharing alliance (comprising the US, Canada, UK, Australia, and New Zealand).

Interestingly, the recent leaking of diplomatic cables suggests that the banning of nuclear warships and subsequent termination of ANZUS with the US was driven by economic considerations as well as ideology. A cable from the US embassy in Wellington read:

“one of the considerations favouring the policy was that it would lead to New Zealand withdrawing or being pushed out of ANZUS, thereby lessening the country’s defence spending requirements at a time of fiscal and economic crisis” (Quote from here)

7. New Zealand’s landscape is as diverse as a continent

I was stunned by the variety of landscape packed into New Zealand’s two islands. In this small space, New Zealand is home to:

- Volcanoes, some of which are still active (see e.g. Tongariro National Park, which I did not have time to visit)

- Temperate rain forest (on North and South Islands)

- The Southern Alps, a mountain range formed by the collision of tectonic plates

- Pristine sand beaches (see Abel Tasman National Park, or Ninety Mile Beach on the North Island)

- Fjords carved by glaciers (see Fjordland National Park, and Milford Sound)

- And of course, Hobbiton (near Rotorua)

Beach at Abel Tasman National Park

Southern Alps while flying into Queenstown

Milford Sound

Hobbiton

Visit if you can!